One hears of scientists, musicians and other innovative beings who are oblivious to the enormity of their work — simply because they have been busy creating for the pure joy of it.

Something similar can be said of Gujarat-based artist Gulam Mohammed Sheikh. At 87, the artist who still paints, is not only known for his art, but also his works of prose. Yet, not many are aware of his fascination for prints.

Handprints, the first of a two-part retrospective features as many as 60 prints, selected from works dating back to 1965 when Gulam was still a student, to the present day. “There is a huge body of work spanning seven decades and none of us knew about its entirety, since he is primarily known as an artist and art critic. I’ve been his student and have known him since 1977, but apart from the occassional prints hanging in his house or seen at shows, the bulk of these have not been exhibited,” says artist Pushpamala N, who curated the show.

Pushpamala says a chance conversation about holding a show of Gulam’s paintings in Bengaluru, led to the revelation that he had never exhibited his prints in a solo show.

Gulam Mohammed Sheikh and Pushpamala N

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

Printmaking is the process of creating artworks by printing, not only on paper, but also on fabric, wood, metal, and other surfaces. Some traditional printmaking techniques are woodcut, linocut, etching, aquatint and lithography, while modern-day methods include screen and digital printing.

“Since prints are created in multiples using different techniques, there were so many of them that we had to exhibit them in two parts. Part one titled Handprints are those pieces executed using the traditional approach,” she says.

In context

“I’ve contextualised his works for this show since he is not only a celebrated artist, but also a poet and writer, an art historian and influential teacher; all these facets come out in these works.”

Pushpamala says Gulam began writing and painting simultaneously, finding his own language and style, and developing it along the way. “He began writing his memoirs in the late 60s, going on to publish it 40 years later,” she says, adding literary and historical references appear in his work in the interim.

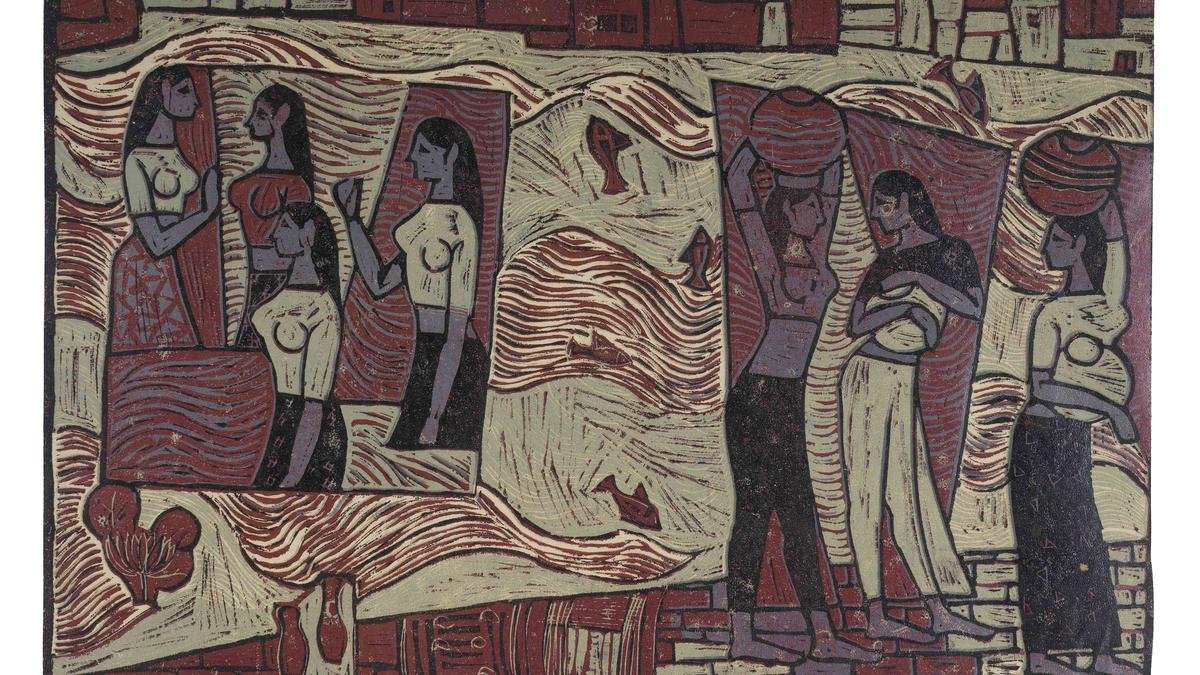

Speaking Tree, silk screen, from Handprints, a retrospective on Gulam Mohd Sheikh.

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

For instance, his work The Riot, is a response to the violent communal riots in Baroda that occurred in 1968-69. “Gulam had always thought of himself as a Nehruvian secularist in a world that was open and where everything was free. At that point, however, he suddenly realised he was ‘The Other’, especially during those riots.”

Yet, Gulam’s depiction is not just a vignette from his life — it is also homage to a famous Mughal folio titled Hamzanama. This 16th century work brought out under Emperor Akbar is not very well known, but since Gulam was teaching art history, he came across this work which intrigued him.

Pushpamala says she has shown his work in chronological order, connecting them to his own history and to events that happened at the time. “I also see it as pedagogy. A lot of students come to the show and the works are a testament to Gulam’s enthusiastic attitude. He loves working with different techniques and media, experimenting with anything new he hears about.”

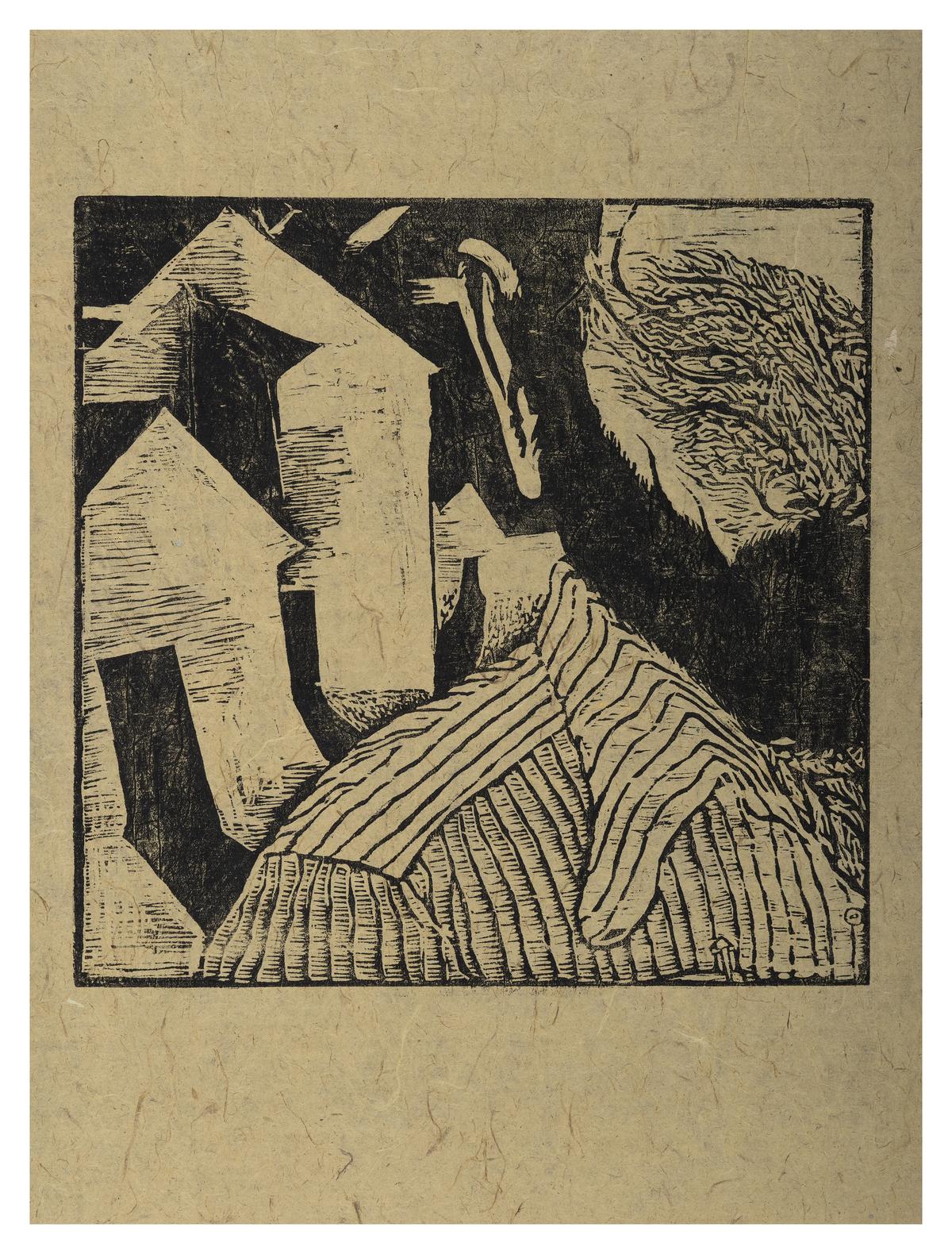

Untitled woodcut from Handprints, a retrospective on Gulam Mohd Sheikh

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

The wealth of woodcut, linocut, etching-aquatint, lithography and silkscreen works on display at Handprints are testament to his prowess.

Throw back to the past

Handprints also features hand written magazines, comic strips and illustrations done by Gulam as a schoolboy. “I believe young artists of today who bring out zines will relate to his work,” says Pushpamala.

By the time he was 15, Gulam was illustrating Pragati, his school’s literary magazine, moving on to Kshitij, an avant garde literary magazine when he was art student. By then he had learnt the art of printmaking and editions in Kshitij, which carried his poetry and prose, benefitted from lino cuts and other illustrations contributed by him and fellow editors.

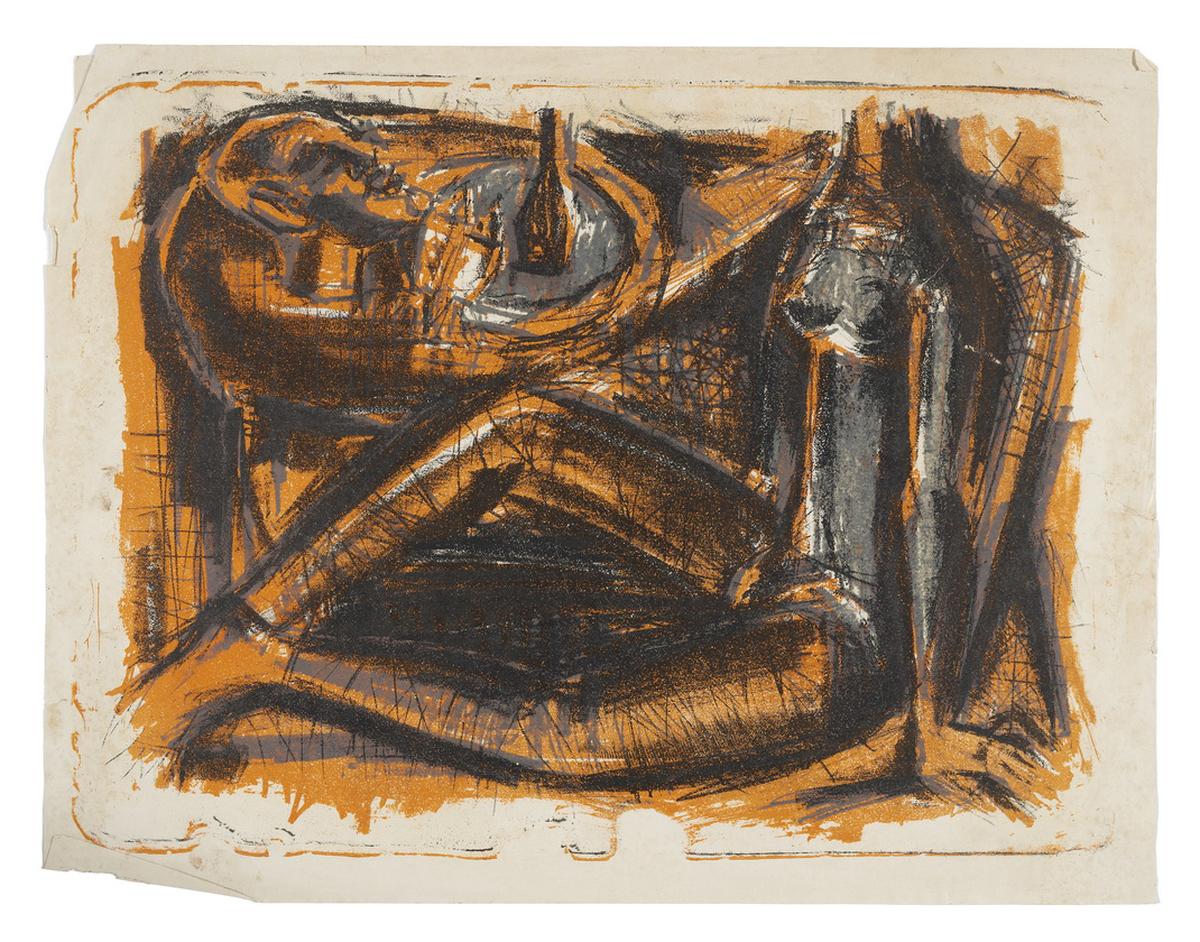

Female figure with Still Life, lithograph, from Handprints, a retrospective on Gulam Mohd Sheikh

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

Gulam also established a magazine Vrishchik with Bhupen Khakhar while teaching art history in Baroda. The periodical which aimed to initiate debate, dialogue and discussion among the art community, had linocuts and lithographs as covers as well as pull outs.

Pushpamala believes this is how Gulam’s art was disseminated in various ways into the literary and public spheres.

Up next

Mindprints or the second part of this retrospective which will go on display from August 17 is more contemporary and colourful. “The first part is monochromatic because of the nature of traditional printmaking techniques,” says Pushpamala.

Pushpmala adds that Mindprints comprises digital prints. “Gulam is one of the pioneers of this technique in India. having begun working on it from the late 90s and 2000s. That is when the technology first came in — people were suspicious of this mode then and rubbished his work at the time.”

Gulam’s fondness for pre-Renaissance art from the West, Persia, Turkey and China, come out in his contemporary work as do autobiographical references to his family and friends. His perspective on cities and fascination with maps have also been documented in Mindprints.

Pushpamala says Gulam’s depiction of cities is not a realistic perspective, but rather a distorted imagery. “One can get glimpses of magic realism and miniatures in his maps, some of which open up like books. In others, images of snakes and ladders decorate the borders or outlines of a city”

“Sometimes, you are looking into a courtyard and something is happening all around it. At times it is not a direct reference — Gulam is referencing different kinds of paintings and historical events.”

A 45-minute video of Gulam in conversation with artist Vasudevan Akittham is running at the exhibition.

Handprints, a retrospective of artist Gulam Mohammed Sheikh is on at Gallery Sumukha till Juy 27.

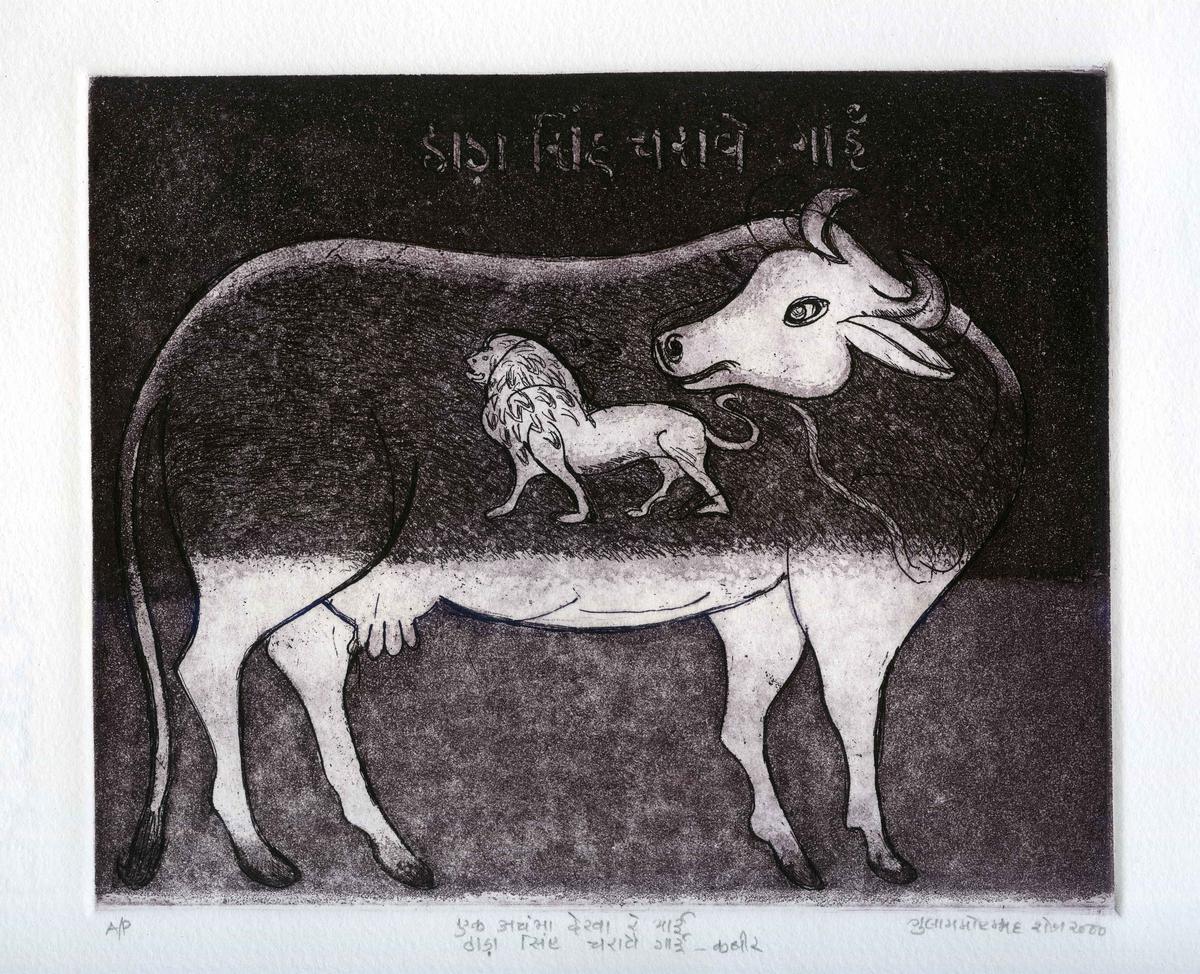

Ek Achambha Dekha re Bhai, etching-aquatint, from Handprints, a retrospective on Gulam Mohd Sheikh

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement